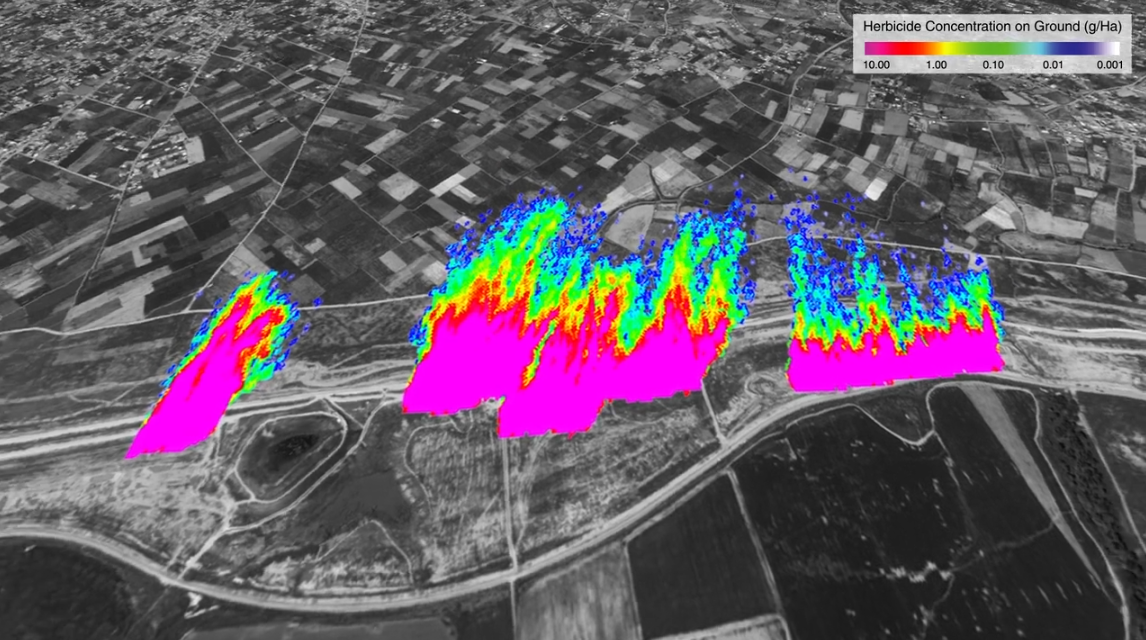

Satellite image of herbicide concentration on the Israel-Gaza border. (Forensic Architecture report video)

Rob Goyanes, Jewish Currents, September 9, 2019

FOR CENTURIES, the plains that comprise modern-day Gaza were lush with citrus orchards. Though early Zionists claimed to have pioneered the orange industry, Palestinian farmers had maintained orange groves—specifically of the sweet “Jaffa” orange that would later be co-opted as a symbol of Israeli ingenuity—for export since the 1800s. In some cases, these orchards were passed down by generations of Palestinian families. Arabs and Jews set up mutual orange enterprises in the early 20th century, but things started to change following Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, and especially following the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

Citriculture largely disappeared from Gaza in the second half of the 20th century, due in large part to Israeli bulldozing of the orange groves. Through the course of investigating the disappearance of the orchards, a researcher with Forensic Architecture—a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London, composed of architects, software developers, and others who investigate human rights violations—learned that the low-lying crops that replaced the groves in recent years were potentially dying due to Israeli actions. This prompted the agency to take a closer look at crop disappearance in Gaza.

In July, Forensic Architecture released a report titled “Herbicidal Warfare in Gaza,” detailing the results of their investigation, which finds that the crop deaths were caused by herbicides sprayed by Israel and carried into Gaza by the wind. The findings raise the disturbing possibility that the Israeli military has been engaging in a form of ecological warfare (a possibility first reported by +972 Magazine in 2015).

“The actual campaign against the citrus was sustained during the Oslo and Madrid peace processes,” says one of the researchers, who asked not to be named because of safety concerns (the report itself was not published anonymously, and lists all participating researchers by name). During the peace processes in the 1990s, he adds, Israeli bulldozers systematically destroyed orange groves. Israel claimed this was necessary because “orange groves were used as a shelter for terrorists.”

Israel occupied and illegally settled Gaza between 1967 and 2005, after which it pulled out its settlements. Israeli bulldozing during this period was a significant factor in the decimation of Palestinian orange orchards, and Gazans typically didn’t have the money or resources to maintain the groves that were left. Soon, according to the researcher, Palestinian farmers began gradually replacing citrus trees with crops that couldn’t be said to provide cover for terrorists, and were cheaper to maintain, including strawberries, cherry tomatoes, and herbs.

Ever since Hamas took power in Gaza in 2007, Israel has maintained a crippling economic blockade, accompanied by periodic bombing campaigns that have killed thousands of civilians. Israel has established and patrolled a “buffer zone,” up to 300 meters or more in some areas, which stretches the entire length of the Gaza side of the border since 2014—roughly the time when a significant number of the lower-growing crops grown by Palestinian farmers close to the border started to die. According to farmers’ testimony—which appears in the Forensic Architecture report and has also been reported on elsewhere—land in the buffer zone, which was previously used by Palestinians as agricultural and residential space, has been razed and bulldozed regularly by the Israeli military for the purpose of surveillance and military operations. When the crops started dying, farmers saw planes spraying herbicides over the Israeli side of the buffer zone, and they assumed the herbicides were to blame.

Working with several NGOs and Palestinian ministries, the researcher collected leaf samples, testimonies, and video footage. Based on a visualization technology called Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI, a remote sensing tool that uses satellite imagery to measure the health of vegetation), it’s clear that there was significant crop loss during the years that the Israeli military was spraying herbicides, from 2014 to 2018. The images, captured in the days after the sprayings, show many red patches throughout the farmlands, indicating loss of vegetation.

With further analysis provided by a fluid dynamics expert, Forensic Architecture concluded that the herbicides—including glyphosate, the primary chemical in the weedkiller Roundup—were being carried by the wind onto Palestinian farmlands a few hundred meters away, and that they were having a significant negative impact on crops.

This appears to have been no accident. “Every single farmer I’ve spoken with says that before each spraying they see a plume of smoke coming,” the researcher says, adding that the sprayings happen without any warning to the farmers. “The Israeli army, in the information they’ve given us through the Freedom of Information request, admitted that among the preparations that they practiced on the ground prior to spraying, incendiary tires was one of them.” Incendiary tires are tires that are burned to determine the direction of the wind. In this case, it seems they were used to ensure that when sprayings occurred, they went toward Gaza, rather than Israel.

According to Forensic Architecture’s researcher, some Palestinian farmers have said that they’ve lost between half a million and a million shekels’ worth of crops since 2014, or approximately $140,000 to $280,000—significant sums considering that Gaza is under an economic blockade, and that nearly 70% of Gaza’s population is classified as food insecure. “It’s not really so much about what’s going to be exported, it’s more that people rely on these crops,” the researcher says.

In 2014, eight Palestinian farmers sought compensation for crops damaged by Israeli herbicide spraying, but all were rejected; according to Israel’s Civil Damages Order, Israel is “not liable for damage to the residents of the Gaza Strip.” In 2015, a kibbutz on the Israeli side, which had also sustained damage to its crops from the military spraying of herbicides, was initially denied compensation on the basis that it was already receiving compensation for its proximity to Gaza. Besides the damage to crops, Kibbutz Nahal Oz argued that the herbicides also lead to land toxicity, preventing the planting of watermelons. The kibbutz ultimately won about $16,000 in compensation from the Israeli Ministry of Defense.

I asked the Israeli Ministry of Defense a series of questions about the use of herbicides, and it responded with the following statement: “The defense establishment conducts weed control, in which the material is sprayed from the air, for operational purposes—among them, removing potential cover for terror elements, which may threaten the citizens of the State of Israel (particularly the communities living adjacent to the Gaza border), as well as IDF troops.” It added that the spraying of herbicides “is conducted only over the territory of the State of Israel. It is carried out by companies specialized in the field, in accordance with the law.” Indeed, the spraying is occurring on the Israeli side of the border—but borders are porous, and they do not stop harmful chemicals carried by the wind. The Ministry did not respond to repeated requests for clarification regarding the burning of tires to assess wind direction.

When the Israeli Ministry of Defense says that it carries out the sprayings “in accordance with the law,” it is unclear whether they mean domestic law, international law, or both (human rights groups have maintained that Israel is breaking both by doing so). In 1977, the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques, an international treaty on ecological warfare, banned “any technique for changing—through the deliberate manipulation of natural processes—the dynamics, composition or structure of the Earth, including its biota, lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere, or of outer space.” Though Israel is not a signatory to this convention, the practice of spraying herbicides for military purposes does seem to fit the definition of such a technique. (The United States is a signatory to the treaty, as well as Israel’s major military ally and patron. The US State Department ignored repeated requests for comment on Israel’s use of the practice.)

Even if Israel had been a signatory, experts have commented that the Environmental Modification Convention is “ultimately toothless,” due to its overly comprehensive language (it fails to mention a single specific technique that might fit the definition) and the lack of transparency into military operations. There is also the fact that all types of warfare are incredibly destructive to the environment, both in terms of the resources needed to maintain modern militaries and in terms of their actual use in combat.

When asked if calling the practice “warfare” in the report was in any way misleading, the researcher responds: “The importance of calling it warfare is that there is a long history of using herbicides as part of armed conflict, whether it’s the British in Malaysia, the Americans in Vietnam, Colombia spraying over the border in Ecuador, or Israel spraying in Gaza.” Still, the researcher expresses ambivalence about the deliberateness with which this campaign is being carried out by the Israeli military: “I don’t think they’re doing it to intentionally harm Gazan farmlands, I think they actually—and this is my opinion—just don’t care that it harms Gazan farmlands, so long as it is flattening the space.”

Deliberate or not, the damage is certainly worsened by the Israeli military’s choice to spray by air, when the spraying could conceivably be done by truck in a more targeted manner. “The way that they’re spraying it makes it largely uncontrollable,” the researcher says. (The Israeli Ministry of Defense did not address questions about why it has sprayed aerially.)

So far in 2019, no sprayings have been reported. There has been no explanation from the Israeli Ministry of Defense about why. Though this is good news for the farmers, it also speaks to the intense psychological component of the practice—the effect on the farmers of not knowing when, or if, the sprayings will start again. Meanwhile, Palestinian farmers across the region continue to face daily threats as they pursue their livelihoods.

“Farmers that I have met, many of them Bedouin women, are repeatedly showing me bullet wounds or shrapnel wounds [or] telling me stories of being shot at only for walking along their farmland, or harvesting their crops,” the researcher says.

Israel’s apparent weaponization of herbicides is just one element of the blockade, with all the violence that it entails. Whether this weaponization is deliberate or simply the product of criminal neglect, it appears to be a continuation of ecological violence, the kind that resulted in the destruction of Gaza’s orange groves.

Rob Goyanes is a writer and editor living in Ridgewood, Queens. His work has appeared in The Miami Herald, Art in America, Los Angeles Review of Books and elsewhere. He tweets @RobGoyanes.