A cantankerous Israel critic takes a rare turn in the limelight.

Norman Finkelstein is crouched on the floor of his apartment, running his fingers along a bookshelf so overcrowded that it’s bending into a U-shape. “It has a green cover,” he assures me before landing on the spine of his tenth book, Knowing Too Much: Why the American Jewish Romance With Israel Is Coming to an End. The subtitle stands as a summation of Finkelstein’s career, which has been devoted to proclaiming to his fellow Jews and others his disenchantment with the Jewish state. But right now, he’s thumbing through the book for proof that Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, was a guard at Israel’s biggest prison camp during the early 1990s, when many Palestinians were tortured there.

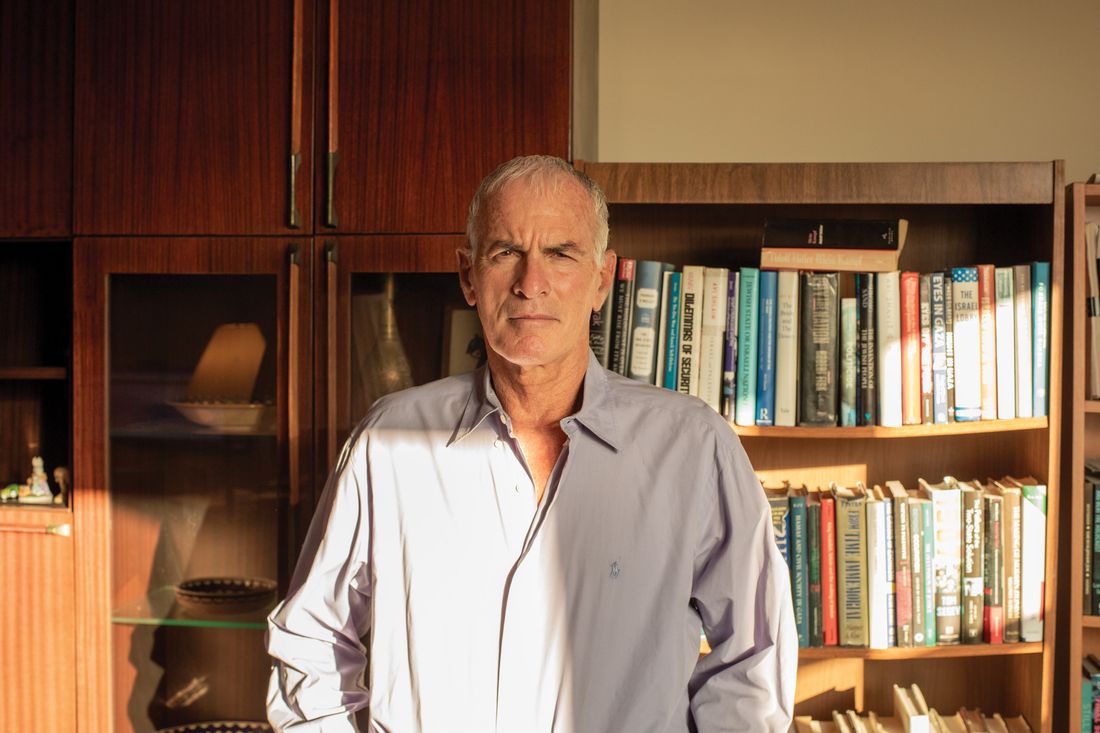

I already know about this story (it’s in Goldberg’s memoir), but Finkelstein, 69, is not used to a world in which people are inclined to believe him. As America’s most divisive Israel-Palestine scholar, he spent the past 40 years being ostracized by the media and academia. Then the October 7 Hamas attack propelled him into the spotlight and his 13th book, Gaza: An Inquest Into Its Martyrdom, into the top-selling spot in Amazon’s Middle Eastern History category. True, there aren’t many books about Gaza (“That’s like being the tallest building in Wichita,” Finkelstein says), but its success is being seen as a vindication by both his longtime and newfound followers.

More

He hasn’t held a steady academic job since DePaul University denied him tenure under political pressure in 2007. Now, after years of sporadic work and low pay as an adjunct, Finkelstein is suddenly spending ten hours a day fielding emails from people clamoring for his insights. “It’s become a complete nightmare,” he says, scrolling through hundreds of new messages in his inbox. His heavily trafficked X account (380,000 followers) and Substack (over 15,000 subscribers) — both run by a three-person technical staff that is paid from subscription revenue — are a torrent of grim facts and sardonic quips about the Israel-Hamas war. (“IDF ‘Searching’ for Hamas Command-and-Control Center Under Al-Shifa Hospital,” reads a typical caption alongside a video of the Seven Dwarfs singing “Heigh-Ho.”)

Finkelstein is five-foot-ten and fit with the angular jawline of a retired drill sergeant. He has short white hair and dark eyebrows and speaks in unhurried paragraphs even when he’s debating Piers Morgan on television — a man unafraid to be long-winded. His warbling Brooklyn accent is a relic from the days when he roamed the halls of James Madison High School, which counts Bernie Sanders and Chuck Schumer among its alumni. He takes regular five-mile jogs along Coney Island Beach and keeps a desktop folder of photos of himself posing in front of the sunset.

Finkelstein is reflective and slightly melancholic in private conversation, but his public reputation is as someone who will browbeat you into submission. (An X user recently observed that he “comes off super radical on basically the strength of being very rude.”) One YouTube video shows him at a 2003 talk at the University of Waterloo. He’s berating an audience member over her “crocodile tears” for Israel, declaring, “My late father was in Auschwitz. My late mother was in Majdanek concentration camp” — he pauses to bark at a heckler to “please shut up” before continuing — “and it is precisely and exactly because of the lessons my parents taught me and my two siblings that I will not be silent when Israel commits its crimes against the Palestinians.”

When he was a child, Finkelstein’s mother would have visceral reactions to injustice, especially to TV reports about violent conflict, which she’d experienced firsthand growing up in wartime Poland. “She physically could not watch it,” Finkelstein says. He inherited her indignation, and as a student inspired by the civil-rights movement, he dived into protests against the Vietnam War. He became too involved, his mother concluded. “She thought I was destroying my life, and there was a feeling that she was responsible for it,” he says.

He wouldn’t actually destroy his life until several years later. In 1984, when he was a doctoral student at Princeton, Finkelstein investigated the sourcing of a celebrated new book by the journalist Joan Peters called From Time Immemorial. Peters argued that Palestinians didn’t actually exist and that Zionist colonization had lured non-native Arabs into the region, where they started waging war on the Israelis. It was mostly a fabrication, Finkelstein discovered, based on fudged demographic data, but a consensus had already formed that this was a monumental work; it was gushed over by the likes of Saul Bellow and Elie Wiesel. Initially, no U.S. publication would touch Finkelstein’s findings (In These Times eventually published them), nor would any American academic except for Noam Chomsky, who became his mentor. “You’re going to expose the American intellectual community as a gang of frauds, and they are not going to like it,” Chomsky warned his protégé. “And they’re going to destroy you.”

It was a frosty introduction to a profession that still seems intent on freezing Finkelstein out, even decades after Peters’s work was widely discredited. He kept writing books and papers that made people angry — his most controversial work, 2000’s The Holocaust Industry, argued that the memory of Jewish genocide was being politically exploited by Israel — but landed a full-time job teaching political science at DePaul in Chicago. “DePaul wanted to get rid of me from the get-go,” Finkelstein says matter-of-factly. In 2003, he accused the lawyer Alan Dershowitz of plagiarism for lifting citations from Peters’s book for his own polemic, The Case for Israel. Thus began one of academia’s all-time bitter feuds: Dershowitz even lobbied California’s then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to stop the publication of one of Finkelstein’s books. (Schwarzenegger declined to intervene.) Finkelstein denounced Dershowitz’s work — “If Dershowitz’s book were made of cloth, I wouldn’t even use it as a schmatta,” he said — and dedicated himself to debunking it until he went up for tenure in 2007. His department and college at DePaul voted to grant it, but the university-level tenure board rejected him following a high-profile campaign by Dershowitz. (The university’s president denied that outside pressure had anything to do with the decision.)

“I live a very simple life,” Finkelstein says of how he survived the intervening years, during which his annual income was sometimes less than $5,000. His apartment is rent-stabilized — he took it over from his father, who died, along with his mother, in 1995 — and it doesn’t look like he’s bought any new furniture since moving in. Hunter and Brooklyn Colleges throw him a teaching gig every so often. He admits that he was so deep in the weeds on Israel-Palestine that “even a specialist wouldn’t have been interested” in what he was writing. He learned that his 2019 book — a granular indictment of the International Criminal Court’s head prosecutor — had sold just a few hundred copies. “Why am I doing this?” he asked himself. “Nobody cares.”

But caring about this conflict — stubbornly and single-mindedly, like so many others devoted to this issue, and not without errors of judgment — is the rare constant in Finkelstein’s turbulent life. After three years of saying relatively little about Israel-Palestine, he resurfaced on October 7 singing the praises of Gaza’s “heroic resistance,” only to be sobered later by the extent of the carnage Hamas had wreaked. “Of course they changed,” he says of his initial feelings, but not enough to alter his unyielding beliefs about the root of the conflict’s dynamics. “What,” he asked days later, “were the people of Gaza supposed to do?”

Leave a Reply