British documents reveal US, UK informed of Gaza-to-Egypt plan

Amer Sultan, Middle East Monitor, February 2, 2025

Are Egyptians’ concerns about a potential Trump-backed plan to transfer Palestinians from Gaza to Egypt – particularly Sinai – after Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza is justified?

The simple answer is yes, British documents reveal.

Files unearthed from the British National Archives confirm that Israel developed a secret plan over five decades ago to deport thousands of Palestinian refugees from Gaza to North Sinai, in northeastern Egypt.

The documents also indicate that both the US and the UK were aware of Israel’s plan but chose not to intervene.

After the Israeli army occupied Gaza, along with the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Syrian Golan Heights in the June 1967 war the small enclave became a big security concern for Israel. Its crowded refugee camps became hotbeds of armed resistance to the occupation. From there, resistance operations were launched against the occupying forces and their collaborators.

The UK estimated that when Israel occupied Gaza, there were 200,000 refugees in the enclave from other areas of Palestine, cared for by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), and another 150,000 who were indigenous Palestinian inhabitants of the Strip.

The British reports said that Gaza was not “economically viable due to security and social problems created by camp life and guerrilla activities that caused increasing numbers of casualties.”

Trump’s ‘extremely serious’ Gaza displacement plan is basically a new Nakba

In addition, these reports estimated that during the period between 1968 and 1971, 240 Arab and Palestinian fighters were killed and 878 others were wounded, while 43 Israeli soldiers were killed and 336 wounded in Gaza.

The Arab League then announced its insistence on stopping Israeli activities against Palestinian refugees in Gaza, and decided to “adopt joint Arab measures to support the resistance in the Strip.”

Britain had been concerned about the situation in the occupied Palestinian territories, particularly Gaza. In response to parliamentary questions, the British government told the House of Commons that it was keeping “a very close eye” on developments in the Strip, adding: “We are watching recent Israeli moves with particular interest, and naturally view with concern any action by the Israeli authorities which might adversely affect the welfare and and morale of the Arab [Palestinian] refugee population in the area.”

Meanwhile, the British Embassy in Tel Aviv monitored Israeli moves to displace thousands of Palestinians to El-Arish, located in the north of the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, approximately 54 kilometres from the Gaza-Egypt border.

According to embassy reports, the plan included the “forced transfer” of Palestinians to Egypt or other Israeli territories, in an attempt to reduce the intensity of the resistance operations against the occupation and the security problems facing the occupation authority in the Strip.

In January 1971, Ernest John Ward Barnes, the British ambassador to Tel Aviv, informed his government of Israeli actions aiming at transferring Palestinians from Gaza to El-Arish. “The only questionable Israeli action from the point of view of international law seems to be the resettlement of some Gazan refugees on Egyptian territory at El Arish,” Barnes said in a dispatch to his boss in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

In the same dispatch, the ambassador reported that the Americans were aware of the Israeli actions but they weren’t willing to raise the issue with the Israelis. “We understand that the American Embassy here broadly share the above analysis and have recommended to Washington that they should not take up the Israeli actions in Gaza with the Israel government in any official way,” Barnes said.

Eight months later, in a special report on Gaza, the ambassador informed his minister of the transfer issue, believing that Israelis “exposed themselves to criticism they are riding roughshod over the legal proprieties and creating facts”. He viewed the resettlement of Gazan refugees to Egypt’s El-Arish as “a typical piece of insensitivity to international opinion”.

In early September 1971, the Israeli government confided in the British that there was a secret plan to deport Palestinians from Gaza to other areas, most notably El-Arish.

Then Israeli Minister of Transport and Communications Shimon Peres, who later become the Labor Party leader, defence and foreign minister, prime minister and president of Israel, told the political counselor at the British Embassy in Tel Aviv that “it is time for Israel to do more in the Gaza Strip and less in the West Bank.”

In a report on the meeting, the embassy said that Peres, who was responsible for dealing with the occupied territories, revealed that there was a ministerial committee reviewing the situation in Gaza. He added that the recommendations of the committee “will not be published nor would there be any dramatic announcement of new policy”, confirming that there was “agreement in the cabinet on a fresh and long-term approach to the refugee problem” in Gaza.

The report added that Peres “believes that that approach will lead to a change in the situation within a year or so.”

Justifying the secrecy surrounding the new policy, Peres said that announcing it “will only feed ammunition to Israel’s enemies.”

Asked whether “many people will be transferred to restore peace and viability to Gaza,” Peres said that “about a third of the camp population will be resettled elsewhere in the Strip or outside it.” He stressed Israel’s belief that “there is a need to perhaps reduce the total population by about 100,000 people.”

Peres expressed “the hope of transferring about 10,000 families to the West Bank, and a smaller number to Israel,” but he informed the British that displacement to the West Bank and the lands of Israel “involves practical problems such as high cost.”

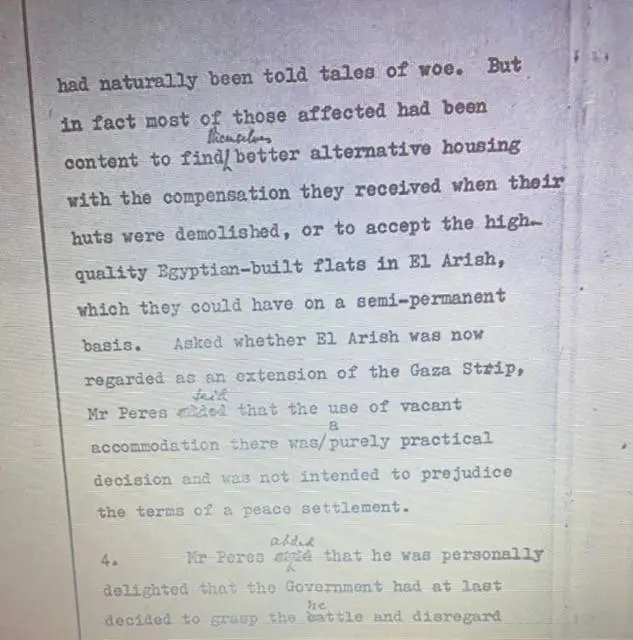

The British diplomat told his bosses in London that “most of those affected are, in fact, content to find themselves better alternative housing with compensation they received when their huts were removed.”

El-Arish was a part of Israel’s “new policy”. Peres pointed out that the affected refugees have also been content to “accept high-quality apartments built by the Egyptians in El Arish, where they can have semi-permanent residence.”

The British diplomat asked the Israeli official: was El-Arish now considered an extension of the Gaza Strip?

“The use of vacant accommodation there was a purely practical decision,” he replied, arguing that this “was not intended to prejudice the terms of a peace settlement.”

In a separate assessment of Peres’s confidential information, the British ambassador to Israel noted that the Israelis believed that any permanent solution to the problems of the Gaza Strip “must include the rehabilitation of part of the population outside its present borders.”

The new policy, he explained, included settling Palestinians in the northern Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, but he said that “the Israeli government risks facing criticism, but the practical results are more important” for Israel.

In a report on the subject, M E Pike, head of the Near East Department at the Foreign Office, said that “drastic measures are now being taken to reduce the size of the refugee camps and open them up. This means forcibly removing refugees from their current homes, or rather their huts, to be more precise, and evacuating them to El Arish in Egyptian territory.”

“A more ambitious resettlement programme now appears to be underway,” he added.

A month later, the Israeli military, in an official meeting, informed a number of foreign military attachés of additional details about the plan to deport Palestinians from Gaza.

During the meeting, Brigadier General Shlomo Gazit, coordinator of Activities in the Administrated (Occupied) Territories, said that his army does not destroy Palestinian homes in Gaza “unless there is alternative housing”, adding that the operation was “limited by the amount of alternative accommodation available within Gaza, including El Arish.”

The Israeli General told the visiting military attachés that 700 of the Palestinian families whose homes were destroyed by the Israeli military in Gaza have found alternative accommodation through their own efforts. “The remainder has been rehoused either within the Gaza Strip or in El Arish,” Gazit added.

According to a report by Colonel P G H-Harwood, the British Air Force attaché, about the meeting, Gazit explained that “the houses in El Arish were chosen because it was the only place with a readily available supply of empty houses in a good state of repair.”

Answering H-Harwood’s question, the Israeli military official said the available houses “were previously owned by Egyptian officers.”

This situation seemed at odds, from the British point of view, with three principles that had been announced by General Moshe Dayan, the Israeli minister of defence, which had guaranteed control over the occupied territories after the 1967 war. These principles were: a minimum military presence, a minimum of interference in normal civilian life and a maximum of contact or open bridges with Israel and the rest of the Arab world.

Ambassador Barnes, in a comprehensive report, warned that his information indicated that UNRWA “anticipates that Israel will resort to the deportation solution”, pointing that the agency “understands the Israeli security problem,” but “cannot agree to the forced transfer of refugees from their homes, nor to their evacuation even on a temporary basis to El Arish in Egypt.”

In its assessment of the secret Israeli plan, the Near East Administration warned that “whatever the Israeli justifications for this far-reaching policy, we cannot help but feel that the Israelis underestimate the extent of the anger that this [Israeli] doctrine of creating facts on the ground will arouse in the Arab world and at the United Nations.”

The documents do not indicate whether the US or the UK communicated with Egypt regarding the Israeli plan.

READ: Is Trump’s lifting of sanctions against Israeli settlers a green light for more violence?

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.