‘Please pass on my deepest fuck you.’

by Rivkah Brown, Novara Media, 18 October 2024

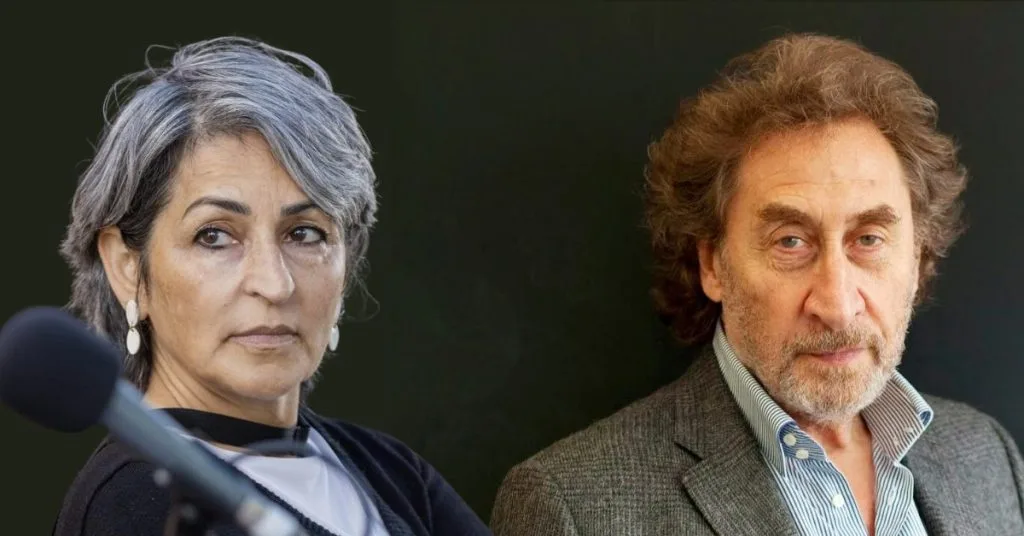

Susan Abulhawa saw the censor’s hand before it even touched her piece. “As the Guardian doesn’t typically publish people like me,” she cautioned her editor at the paper, “I want to be sure the edits don’t ‘dilute’ the piece to make it more palatable for their readers. We know a very different Israel than the one presented by the media for decades, and the tendency is to ‘soften’ Palestinian voices.”

“I absolutely understand and I am going to do my best to protect and fight for your piece,” the series editor V (formerly known as Eve Ensler) assured Abulhawa, adding: “I have the profoundest respect for you and your writing.”

It would be hard not to: Abulhawa’s debut novel Mornings in Jenin has sold over 1m copies in 32 languages since it was published in 2006, making her by some counts the most widely read Palestinian author in history.

Yet by the following month, the Guardian had stopped responding to Abulhawa’s emails.

In July, Guardian US invited Abulhawa to contribute to “rise against fascism”, a series of opinion pieces about the global far right due to be published in September. Abulhawa agreed and submitted a short piece about Israel’s genocide in Gaza, based in part on her own experience: she visited the strip twice this year.

After several rounds of increasingly fraught back-and-forth, the paper and Abulhawa parted ways. The disagreement had centred on Abulhawa’s insistence on using the term “holocaust” to describe Israel’s actions in Gaza. “Israel is committing the holocaust of our time,” Abulhawa wrote in a draft, published today by Novara Media, “and it is doing it in full view of a seemingly indifferent world.” Unable to find an alternative wording that both parties would accept, the Guardian refused the piece.

“Please pass on my deepest fuck you to Betsy [Reed, editor-in-chief of Guardian US] and her racist core,” Abulhawa wrote in her final email. Yet it wasn’t Reed who had ultimately spiked the piece: Katharine Viner, the Guardian’s global editor-in-chief, had intervened at the eleventh hour.

Six Guardian journalists who spoke to Novara Media said they understood why Viner had resisted Abulhawa’s use of the term “holocaust”; doing so would have kicked off a media storm. What they don’t understand is why Viner seems happy to repeatedly weather such storms for advocates of Israel. This, they suggest, points to a pattern of deference towards the paper’s pro-Israel critics, one that has shifted only slightly as Israel’s assault on Gaza has intensified.

“Is the Guardian more worried about the reaction to what is said about Israel than Palestine? Absolutely,” said one long-serving staff member.

The Guardian did not respond to Novara Media’s request for comment.

Rationalising infanticide

After 7 October, staff say that the Guardian’s editor-in-chief has maintained a vice-like grip over the paper’s output on Israel and Palestine – or at least one side of it. Some desks say that in the initial weeks and months following the Hamas attack, every piece on the subject was sent to Viner for approval, delaying and sometimes halting publication.

“Everything is scrutinised,” said one senior staff member. “You’re under such an amount of suffocating control, it’s like throwing sand in the gears [to] deliberately… frustrate the smooth running [of the paper].”

In two cases, Viner overruled section editors to withdraw pieces by Palestinian contributors, Abulhawa and Dylan Saba. Both were commissioned by the Guardian US, whose distance from the paper’s London headquarters has emboldened it to push left on certain issues where the UK edition tends right (notably gender, though also Palestine).

Viner’s censoring instinct has been perhaps clearest in her treatment of Owen Jones: Viner is widely understood to have banned the longstanding Guardian columnist from writing about Palestine between late November and mid-January, during some of the most intense months of Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip.

One senior staffer pointed out that Viner’s control is not exercised consistently, however – “only if you’re publishing something critical of Israel.”

The Guardian publishes few if any pieces explicitly defending Israel’s actions in Gaza. Instead, contributors will often claim that criticism of Israel is cover for the “new antisemitism” – or “alibi antisemitism”, as Dave Rich, author of The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism, described it in a recent Guardian op-ed.

“It’s a perverse landscape right now, where it’s not… that you’re pro-Palestine or pro-Israel,” said one senior staffer. “You’re pro-Palestine or you’re anti-antisemitism.” Howard Jacobson’s piece fell into the latter category.

On 6 October, the day before the anniversary of the Hamas attack on Israel’s Gaza borderlands, the Observer published a piece by the acclaimed British Jewish author (the Observer shares an owner with the Guardian, though in mid-September it emerged that Guardian Media Group was in talks with media startup Tortoise Media to sell the Sunday paper; the paper has its own editor-in-chief, though in reality Viner has final say in what is published in both papers). The piece argued that the media’s attempts to draw attention to Israel’s mass killing of Palestinian children – 16,756 have been recorded killed in Israeli attacks since 7 October, though scholarly estimates are far higher – are reviving the antisemitic blood libel that Jews ritually sacrifice children.

“Here we were again, the same merciless infanticides inscribed in the imaginations of medieval Christians,” Jacobson wrote. “Only this time, instead of operating on the midnight streets of Lincoln and Norwich, they target Palestinian schools, the paediatric wards of hospitals, the tiny fragile bodies of children themselves.”

“There has been a massive backlash to it internally,” said one senior Guardian staff member. “People are disgusted and horrified and just dismayed and embarrassed that that was published.” One long-serving Guardian staffer said it was “amazing” that the Observer would publish the piece, which they described as “abominable”. Several Guardian staff and contributors complained about the piece to Observer editor Paul Webster; they received pro forma responses or in some cases, none at all.

The piece attracted widespread scrutiny outside of the Guardian, prompting The New Yorker to run a coruscating interview with Jacobson entitled “Rationalising the horrors of Israel’s war in Gaza”. “Howard, I think maybe we’re in a bit of a worrisome place if you see photos of dead children on television and your first thought is, They’re trying to make me, a Jew, hate my people,” the magazine’s sharp-tongued interviewer Isaac Chotiner challenged Jacobson. The Observer has since published a response to Jacobson by a Jewish contributor, as well as several letters.

One long-serving Guardian journalist suggested the reason the Observer ran the piece is that Jacobson is “supposed to be one of the great writers” and a “staple of the paper”. Jacobson has written for the Observer since at least 2000; between 2017 and 2018 it published a weekly diary by him. Yet while Jacobson’s piece sailed smoothly to publication, another “great writer” was struggling to pass the Guardian’s rigorous – or partially rigorous – editorial process.

‘Please leave this word’

On 13 September, six weeks after she’d filed her piece, Abulhawa received an email from the Guardian with a final round of edits. She accepted almost all of them besides the suggestion to change the word “holocaust” to “genocide”. Abulhawa was confused, since the term hadn’t been picked up in previous rounds of editing.

“Please leave this word,” Abulhawa said in a comment. “It is not the property of any group. It is a word in the English language that is not exclusive to anyone.”

The Guardian pushed back. “We favor substituting ‘genocide’ for ‘holocaust’ there, which is still strong and does not blunt the impact of Susan’s piece,” Guardian US editor Betsy Reed wrote to Abulhawa’s editor, V. Novara Media understand that Reed’s email was sent after consultation with Viner.

V forwarded Reed’s email to Abulhawa, who replied with a five-point explanation of why the term holocaust was appropriate. “Given the magnitude, the unceasing horror, the hateful glee and sadism at our suffering,” Abulhawa wrote, “the only word I have at my disposal that comes close to capturing what’s happening is ‘holocaust’.”

“I understand Susan’s reasoning,” Reed replied, “but I wonder if we could find a solution that captures the meaning she wants without invoking the holocaust in that way.”

Abulhawa refused. “I’ve compromised a lot, but I’m not bending further. We’re watching faceless, headless, limbless, burned, crushed, and mangled bodies in inconceivable gore every day, over and over. … I am not going to play this western media game of tiptoeing around the feelings of our tormentors. Nazis were not so cruel.

“Holocaust is an English word in the English dictionary. It is frankly not big enough to capture the annihilation, torment, degradation, and horror being inflicted on Palestinians for decades now.

“I really don’t care if they run my piece or not.”

Abulhawa sent a further email shortly afterwards: “I’m sick of this hypocrisy. they cannot fathom our humanity. That’s the issue. They do not see us as human. If our people in Gaza were Jewish, or other Europeans, no one would hesitate to use that word and worse.”

After receiving no reply from V for over a week, Abulhawa inquired about the status of her piece. V confirmed that the Guardian had declined to run it: “They don’t seem to be budging on the last edits. The world is a horror. Thank you for your courage and voice,” V wrote.

In an email to Novara Media, V wrote: “I commissioned Susan because I believe she is a really important voice on Gaza and Palestine. I believe she wrote an excellent piece; the Guardian, of course, makes the ultimate decisions.”

Abulhawa would not be appeased. “Please pass on my deepest fuck you to Betsy and her racist core,” she replied. The Guardian’s rise against fascism series was published in early September, including 15 pieces on subjects including India, Italy, the climate crisis and human psychology. None were on Israel and Palestine.

In a message to Novara Media, Abulhawa explained why she’d expressed her anger at Guardian editors. “I think Betsy reserves th[e] word [“holocaust”] for one people only. … In [the] western imagination, there is nothing more horrific than the mass slaughter of their own western citizens. Brown people don’t count.”

Several genocide scholars who spoke to Novara Media said they were comfortable with Abulhawa’s use of the term holocaust to describe events in Gaza.

“I accept [the word holocaust] is not the property of any group,” Mark Levene, an emeritus fellow at the University of Southampton whose research focuses on genocide and Jewish history, told Novara Media. “Who am I or who is anybody to deny her?”

“She’s [using the term] for the purpose of making a point, and she has … the perfect right to make the point, even if one might demur on whether [she is correct].”

John Cox, director of Holocaust, genocide and human rights studies at the University of North Carolina, concurred. “I think it’s acceptable to use holocaust to refer to other genocides,” he wrote in an email to Novara Media, “though I do it very sparingly, given the possibility of being misunderstood. But I support Abulhawa’s decision and right to use the term, and I fully agree with the quote from her that you provided.”

Abulhawa had used the term holocaust to describe what she saw in Gaza on several occasions prior to her Guardian piece, including in a video for the leftwing US broadcaster Democracy Now!, an article for pro-Palestine outlet The Electronic Intifada and on her social media channels. But for the Guardian, even “genocide” was a stretch.

Levene had discovered this himself when he submitted a letter to the Guardian on 11 October, four days after the Hamas attack, saying that “Israel is on the cusp of committing genocide in Gaza”; the letter was rejected. It would be several months before the term genocide crept into the paper following the International Court of Justice’s interim judgement in January that said Palestinians had the plausible right to be protected from genocide; it is still understood to be impermissible in the UK edition except with careful explication. The Guardian files coverage of the genocide under a section previously entitled “Israel-Hamas war”, now “Israel-Gaza war”.

One longtime Guardian staff member said they understood Viner’s decision not to allow Abulhawa to use the term holocaust. “Why is she [Abulhawa] so wedded to using this word, knowing how provocative it is for large numbers of Jewish people? Is she through the back door trying to draw a parallel with the Nazi Holocaust?”

They added the paper may have been more cautious with Abulhawa’s piece in order to leave itself latitude to be more forthright in other areas. “I think … they’re buying themselves the ability to say other things by avoiding these fights.”

Another senior Guardian journalist said they felt that “Palestinians are constantly tone-policed in a way no other group is”, though in this case Reed’s suggestion of the word genocide was “perfectly reasonable”. Speaking to Novara Media, they said that including the word holocaust would “completely detract from the piece, because that’s all anyone will talk about”. “It’s a huge uphill battle to get the Guardian to write about genocide,” they added. “Unfortunately, we have to just be a bit practical about how best to get our message across.”

A pattern on Palestine

“I’ve been a writer for a long time,” Abulhawa wrote in a message to Novara Media. “Of course I anticipated they’d reject my piece. … They don’t publish us [Palestinians] unless we accept watered-down versions of what we say so they can pretend to have a semblance of journalistic integrity while they push state and corporate propaganda.”

This was not the first time in recent months that the Guardian has refused to publish pieces by Palestinian contributors at the eleventh hour. In October last year, Viner cancelled a piece by Dylan Saba, a US lawyer with Palestinian and Jewish heritage, about the suppression of pro-Palestine sentiment; a spokesperson for the paper claimed Saba’s piece“did not meet” the Guardian’s “high standards”.

A few weeks after Abulhawa’s run-in with Reed, Stuart Jeffries had his own with Guardian editors in London. The former staffer has worked for the paper since 1990 in various roles, and continues to freelance for it. In early October, the paper published Jeffries’ four-star review of One Day in October, a documentary about the 7 October Hamas attack.

While mostly praising the documentary, Jeffries reserved a single star for what he felt was its failure to contextualise the attack, or to characterise Palestinians as anything other than terrorists. “If you want to understand why Hamas murdered civilians, though, One Day in October won’t help,” Jeffries wrote. “Indeed, it does a good job of demonising Gazans, first as testosterone-crazed Hamas killers, later as shameless civilian looters, asset-stripping the kibbutz while bodies lay in the street and the terrified living hid.”

The review triggered a deluge of criticism, including from former Guardian columnist Hadley Freeman, Jews Don’t Count author David Baddiel, the Telegraph and several Israeli and Jewish media outlets. The review was removed from the paper’s website within a few hours of being published with a note explaining that it was “pending review”.

The Guardian elaborated minimally on this note in a statement to Novara Media, however on Monday, the Guardian readers’ editor Elisabeth Ribbans explained further: “The Guardian considers the article did convey the harrowing footage and powerful survivor interviews and condemned the attack’s perpetrators. But the unacceptable terms in which it went on to criticise the documentary were inconsistent with our editorial standards.

“This was a collective failure of process and we apologise for any offence caused.”

All of the six Guardian journalists who spoke to Novara Media agreed that the treatment of Abulhawa and Jeffries pointed to a stark inconsistency in how the Guardian treats Israel and Palestine.

“Is there a double standard between running Howard Jacobson and not running Susan Abulhawa? Clearly there is, yes,” said one long-serving staffer. “If you’re prepared to run Howard Jacobson then it does seem out of kilter, if your only objection is about that language, then yeah. I understand why that decision might’ve been made, but does it seem that there is an inconsistency there? Yes.”

The roots of this discrepancy reflect a broader media ecosystem, one in which powerful Israel advocacy groups and media monitoring outfits have forced even the most prestigious publications on to the defensive by launching viral smear campaigns and by flooding editors’ inboxes with complaints: on 15 October the New York Times published a response to criticism of a guest essay based on testimony of 65 US-based medical workers who had worked in Gaza, saying that it had photographic evidence to corroborate its claims of Israel’s sniper attacks on children.

Guardian journalists say Viner is particularly susceptible to such targeted campaigns. “Kath just loathes being embarrassed,” one told Novara Media, “and that benefits the pro-Israel lobby, because they’re more powerful and respectable than advocates for Palestine, and can cause her more personal embarrassment.”

A related driver for the Guardian’s caution are fears of antisemitism. Such fears, its journalists say, were exacerbated by the Labour antisemitism crisis to which some see the paper as having contributed. “I think there’s a lot of … fear of dismissing people’s fears of antisemitism [and] of being perceived as antisemitic, and that has unfortunately permeated throughout the whole of journalism,” said one Guardian writer. Others say that Viner’s concerns about being perceived as antisemitic have abated somewhat as Israel’s assault on Gaza has escalated – over the summer the paper changed its style guide to describe the “Hamas-run health ministry” as the “Palestinian ministry of health”, a small but significant break with media convention in the UK.

Nevertheless, says one Guardian journalist, “to have quashed [Jacobson] would’ve been an admission of antisemitism in the eyes of a certain readership, I guess, and in the eyes of the editorial board of the Guardian. I think [the Guardian and Observer] were in an invidious position, because they had a [controversial] article on their hands, and I think they did entirely the wrong thing, [but] put it the other way and they reject Jewish writer’s opinion piece.”

Another Guardian journalist suggested that the paper’s decision to censor Abulhawa is not only demonstrably unfair but also out-of-step with its own audience. “Obviously this is a question of double standards. A Palestinian writer is spiked on the basis that describing a genocide of her own people in [what editors felt were] excessively inflammatory terms isn’t acceptable, then you have someone who isn’t Israeli who has written a piece which doesn’t even try to refute the violent killing of 16,000 children as if [people who draw attention to that fact were] committing a hate crime? I think the Guardian is playing a very dangerous game with its own readership.”

They added that Viner allowing the publication of Jacobson’s piece suggests that the Guardian believes the horrors unfolding in Gaza are a debatable matter – a grotesque notion to much of its audience.

“The Guardian’s readership overwhelmingly would expect the Guardian to take a clear, unambiguous stand about what is clearly a crime of monumental proportions,” they said, “rather than basically suggest[ing] that different people have the right to express different perspectives, up to saying that discussing the biggest slaughter of children in a generation is a hate crime.

“That means that the home of progressive opinion thinks that’s a legitimate position to be debated and discussed. Most Guardian readers would find that abhorrent.”

Rivkah Brown is a commissioning editor and reporter at Novara Media.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.