Introduction

We agree with the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA) of March 25, 2021, “a tool to identify, confront and raise awareness about antisemitism as it manifests in countries around the world today.” The Declaration holds that “while antisemitism has certain distinctive features, the fight against it is inseparable from the overall fight against all forms of racial, ethnic, cultural, religious, and gender discrimination.”

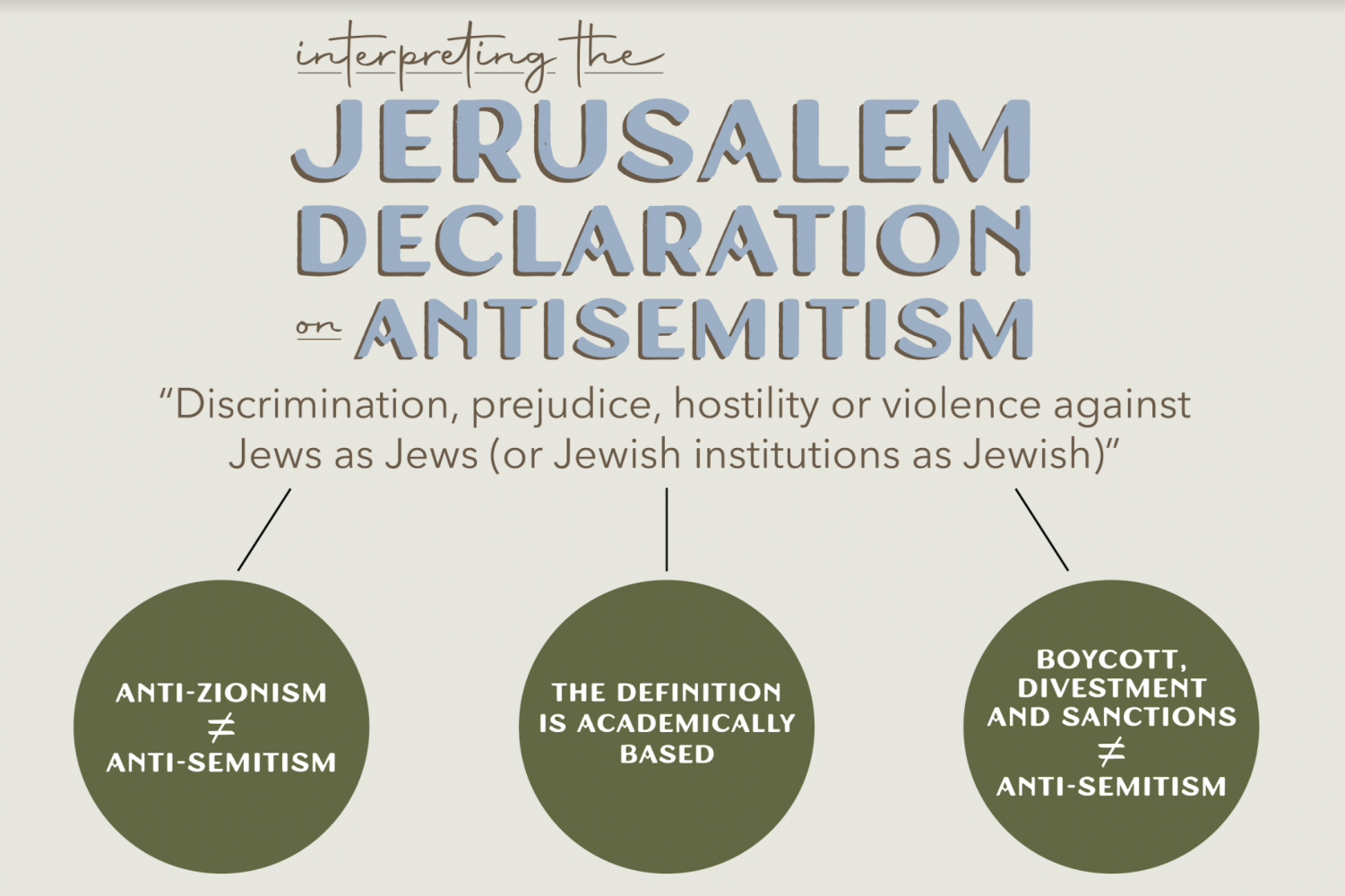

Defining antisemitism as “discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish)”, the JDA gives clear examples of what is, and what is not, antisemitism, paying particular attention to why criticism of Israel or Zionism is NOT inherently antisemitic.

We urge you to read the entire Declaration.

“Antisemitism is discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish).”

People of goodwill seek guidance about the key question:

When does political speech about Israel or Zionism cross the line into antisemitism and when should it be protected?

The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism is a tool to identify, confront and raise awareness about antisemitism as it manifests in countries around the world today. It includes a preamble, definition, and a set of 15 guidelines that provide detailed guidance for those seeking to recognize antisemitism in order to craft responses.

It was developed by a group of scholars in the fields of Holocaust history, Jewish studies, and Middle East studies to meet what has become a growing challenge: providing clear guidance to identify and fight antisemitism while protecting free expression. It has over 200 signatories.

Preamble | Definition | Guidelines | Signatories | FAQ | About JDA | Videos

Preamble

We, the undersigned, present the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, the product of an initiative that originated in Jerusalem. We include in our number international scholars working in Antisemitism Studies and related fields, including Jewish, Holocaust, Israel, Palestine, and Middle East Studies. The text of the Declaration has benefited from consultation with legal scholars and members of civil society.

Inspired by the 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the 1969 Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination, the 2000 Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust, and the 2005 United Nations Resolution on Holocaust Remembrance, we hold that while antisemitism has certain distinctive features, the fight against it is inseparable from the overall fight against all forms of racial, ethnic, cultural, religious, and gender discrimination.

Conscious of the historical persecution of Jews throughout history and of the universal lessons of the Holocaust, and viewing with alarm the reassertion of antisemitism by groups that mobilize hatred and violence in politics, society, and on the internet, we seek to provide a usable, concise, and historically-informed core definition of antisemitism with a set of guidelines.

The Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism responds to “the IHRA Definition,” the document that was adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) in 2016. Because the IHRA Definition is unclear in key respects and widely open to different interpretations, it has caused confusion and generated controversy, hence weakening the fight against antisemitism.

Noting that it calls itself “a working definition,” we have sought to improve on it by offering (a) a clearer core definition and (b) a coherent set of guidelines. We hope this will be helpful for monitoring and combating antisemitism, as well as for educational purposes. We propose our non-legally binding Declaration as an alternative to the IHRA Definition. Institutions that have already adopted the IHRA Definition can use our text as a tool for interpreting it.

The IHRA Definition includes 11 “examples” of antisemitism, 7 of which focus on the State of Israel. While this puts undue emphasis on one arena, there is a widely-felt need for clarity on the limits of legitimate political speech and action concerning Zionism, Israel, and Palestine. Our aim is twofold: (1) to strengthen the fight against antisemitism by clarifying what it is and how it is manifested, (2) to protect a space for an open debate about the vexed question of the future of Israel/Palestine. We do not all share the same political views and we are not seeking to promote a partisan political agenda. Determining that a controversial view or action is not antisemitic implies neither that we endorse it nor that we do not.

The guidelines that focus on Israel-Palestine (numbers 6 to 15) should be taken together. In general, when applying the guidelines each should be read in the light of the others and always with a view to context. Context can include the intention behind an utterance, or a pattern of speech over time, or even the identity of the speaker, especially when the subject is Israel or Zionism. So, for example, hostility to Israel could be an expression of an antisemitic animus, or it could be a reaction to a human rights violation, or it could be the emotion that a Palestinian person feels on account of their experience at the hands of the State. In short, judgement and sensitivity are needed in applying these guidelines to concrete situations.

Definition

Antisemitism is discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish).

Guidelines

A. General

1. It is racist to essentialize (treat a character trait as inherent) or to make sweeping negative generalizations about a given population. What is true of racism in general is true of antisemitism in particular.

2. What is particular in classic antisemitism is the idea that Jews are linked to the forces of evil. This stands at the core of many anti-Jewish fantasies, such as the idea of a Jewish conspiracy in which “the Jews” possess hidden power that they use to promote their own collective agenda at the expense of other people. This linkage between Jews and evil continues in the present: in the fantasy that “the Jews” control governments with a “hidden hand,” that they own the banks, control the media, act as “a state within a state,” and are responsible for spreading disease (such as Covid-19). All these features can be instrumentalized by different (and even antagonistic) political causes.

3. Antisemitism can be manifested in words, visual images, and deeds. Examples of antisemitic words include utterances that all Jews are wealthy, inherently stingy, or unpatriotic. In antisemitic caricatures, Jews are often depicted as grotesque, with big noses and associated with wealth. Examples of antisemitic deeds are: assaulting someone because she or he is Jewish, attacking a synagogue, daubing swastikas on Jewish graves, or refusing to hire or promote people because they are Jewish.

4. Antisemitism can be direct or indirect, explicit or coded. For example, “The Rothschilds control the world” is a coded statement about the alleged power of “the Jews” over banks and international finance. Similarly, portraying Israel as the ultimate evil or grossly exaggerating its actual influence can be a coded way of racializing and stigmatizing Jews. In many cases, identifying coded speech is a matter of context and judgement, taking account of these guidelines.

5. Denying or minimizing the Holocaust by claiming that the deliberate Nazi genocide of the Jews did not take place, or that there were no extermination camps or gas chambers, or that the number of victims was a fraction of the actual total, is antisemitic.

B. Israel and Palestine: examples that, on the face of it, are antisemitic

6. Applying the symbols, images and negative stereotypes of classical antisemitism (see guidelines 2 and 3) to the State of Israel.

7. Holding Jews collectively responsible for Israel’s conduct or treating Jews, simply because they are Jewish, as agents of Israel.

8. Requiring people, because they are Jewish, publicly to condemn Israel or Zionism (for example, at a political meeting).

9. Assuming that non-Israeli Jews, simply because they are Jews, are necessarily more loyal to Israel than to their own countries.

10. Denying the right of Jews in the State of Israel to exist and flourish, collectively and individually, as Jews, in accordance with the principle of equality.

C. Israel and Palestine: examples that, on the face of it, are not antisemitic

(whether or not one approves of the view or action)

11. Supporting the Palestinian demand for justice and the full grant of their political, national, civil and human rights, as encapsulated in international law.

12. Criticizing or opposing Zionism as a form of nationalism, or arguing for a variety of constitutional arrangements for Jews and Palestinians in the area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean. It is not antisemitic to support arrangements that accord full equality to all inhabitants “between the river and the sea,” whether in two states, a binational state, unitary democratic state, federal state, or in whatever form.

13. Evidence-based criticism of Israel as a state. This includes its institutions and founding principles. It also includes its policies and practices, domestic and abroad, such as the conduct of Israel in the West Bank and Gaza, the role Israel plays in the region, or any other way in which, as a state, it influences events in the world. It is not antisemitic to point out systematic racial discrimination. In general, the same norms of debate that apply to other states and to other conflicts over national self-determination apply in the case of Israel and Palestine. Thus, even if contentious, it is not antisemitic, in and of itself, to compare Israel with other historical cases, including settler-colonialism or apartheid.

14. Boycott, divestment and sanctions are commonplace, non-violent forms of political protest against states. In the Israeli case they are not, in and of themselves, antisemitic.

15. Political speech does not have to be measured, proportional, tempered, or reasonable to be protected under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and other human rights instruments. Criticism that some may see as excessive or contentious, or as reflecting a “double standard,” is not, in and of itself, antisemitic. In general, the line between antisemitic and non-antisemitic speech is different from the line between unreasonable and reasonable speech.

Signatories

Ludo Abicht, Professor Dr., Political Science Department, University of Antwerp

Taner Akçam, Professor, Kaloosdian/Mugar Chair Armenian History and Genocide, Clark University

Gadi Algazi, Professor, Department of History and Minerva Institute for German History, Tel Aviv University

Seth Anziska, Mohamed S. Farsi-Polonsky Associate Professor of Jewish-Muslim Relations, University College London

Aleida Assmann, Professor Dr., Literary Studies, Holocaust, Trauma and Memory Studies, Konstanz University

Jean-Christophe Attias, Professor, Medieval Jewish Thought, École Pratique des Hautes Études, Université PSL Paris

Leora Auslander, Arthur and Joann Rasmussen Professor of Western Civilization in the College and Professor of European Social History, Department of History, University of Chicago

Bernard Avishai, Visiting Professor of Government, Department of Government, Dartmouth College

Angelika Bammer, Professor, Comparative Literature, Affiliate Faculty of Jewish Studies, Emory University

Omer Bartov, John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor of European History, Brown University

Almog Behar, Dr., Department of Literature and the Judeo-Arabic Cultural Studies Program, Tel Aviv University

Moshe Behar, Associate Professor, Israel/Palestine and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Manchester

Peter Beinart, Professor of Journalism and Political Science, The City University of New York (CUNY); Editor at large, Jewish Currents

Elissa Bemporad, Jerry and William Ungar Chair in East European Jewish History and the Holocaust; Professor of History, Queens College and The City University of New York (CUNY)

Sarah Bunin Benor, Professor of Contemporary Jewish Studies, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion

Wolfgang Benz, Professor Dr., fmr. Director Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universität Berlin

Doris Bergen, Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe Professor of Holocaust Studies, Department of History and Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Toronto

Werner Bergmann, Professor Emeritus, Sociologist, Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universität Berlin

Michael Berkowitz, Professor, Modern Jewish History, University College London

Lila Corwin Berman, Murray Friedman Chair of American Jewish History, Temple University

Louise Bethlehem, Associate Professor and Chair of the Program in Cultural Studies, English and Cultural Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

David Biale, Emanuel Ringelblum Distinguished Professor, University of California, Davis

Leora Bilsky, Professor, The Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University

Monica Black, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Daniel Blatman, Professor, Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Omri Boehm, Associate Professor of Philosophy, The New School for Social Research, New York

Daniel Boyarin, Taubman Professor of Talmudic Culture, UC Berkeley

Christina von Braun, Professor Dr., Selma Stern Center for Jewish Studies, Humboldt University, Berlin

Micha Brumlik, Professor Dr., fmr. Director of Fritz Bauer Institut-Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust, Frankfurt am Main

Jose Brunner, Professor Emeritus, Buchmann Faculty of Law and Cohn Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science, Tel Aviv University

Darcy Buerkle, Professor and Chair of History, Smith College

John Bunzl, Professor Dr., The Austrian Institute for International Politics

Michelle U. Campos, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and History Pennsylvania State University

Francesco Cassata, Professor, Contemporary History Department of Ancient Studies, Philosophy and History, University of Genoa

Naomi Chazan, Professor Emerita of Political Science, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Bryan Cheyette, Professor and Chair in Modern Literature and Culture, University of Reading

Stephen Clingman, Distinguished University Professor, Department of English, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Raya Cohen, Dr., fmr. Department of Jewish History, Tel Aviv University; fmr. Department of Sociology, University of Naples Federico II

Alon Confino, Pen Tishkach Chair of Holocaust Studies, Professor of History and Jewish Studies, Director Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Sebastian Conrad, Professor of Global and Postcolonial History, Freie Universität Berlin

Deborah Dash Moore, Frederick G. L. Huetwell Professor of History and Professor of Judaic Studies, University of Michigan

Natalie Zemon Davis, Professor Emerita, Princeton University and University of Toronto

Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, Professor Emerita, Comparative Literature, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Hasia R. Diner, Professor, New York University

Arie M. Dubnov, Max Ticktin Chair of Israel Studies and Director Judaic Studies Program, The George Washington University

Debórah Dwork, Director Center for the Study of the Holocaust, Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Graduate Center, The City University of New York (CUNY)

Yulia Egorova, Professor, Department of Anthropology, Durham University, Director Centre for the Study of Jewish Culture, Society and Politics

Helga Embacher, Professor Dr., Department of History, Paris Lodron University Salzburg

Vincent Engel, Professor, University of Louvain, UCLouvain

David Enoch, Professor, Philosophy Department and Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Yuval Evri, Dr., Leverhulme Early Career Fellow SPLAS, King’s College London

Richard Falk, Professor Emeritus of International Law, Princeton University; Chair of Global Law, School of Law, Queen Mary University, London

David Feldman, Professor, Director of the Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, Birkbeck, University of London

Yochi Fischer, Dr., Deputy Director Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Head of the Sacredness, Religion and Secularization Cluster

Ulrike Freitag, Professor Dr., History of the Middle East, Director Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin

Ute Frevert, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin

Katharina Galor, Professor Dr., Hirschfeld Visiting Associate Professor, Program in Judaic Studies, Program in Urban Studies, Brown University

Chaim Gans, Professor Emeritus, The Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University

Alexandra Garbarini, Professor, Department of History and Program in Jewish Studies, Williams College

Shirli Gilbert, Professor of Modern Jewish History, University College London

Sander Gilman, Distinguished Professor of the Liberal Arts and Sciences; Professor of Psychiatry, Emory University

Shai Ginsburg, Associate Professor, Chair of the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and Faculty Member of the Center for Jewish Studies, Duke University

Victor Ginsburgh, Professor Emeritus, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels

Carlo Ginzburg, Professor Emeritus, UCLA and Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa

Snait Gissis, Dr., Cohn Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Ideas, Tel Aviv University

Glowacka Dorota, Professor, Humanities, University of King’s College, Halifax

Amos Goldberg, Professor, The Jonah M. Machover Chair in Holocaust Studies, Head of the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Harvey Goldberg, Professor Emeritus, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, Professor, Jewish Culture and History, Head of Jewish Studies at the Advanced School of Social Sciences (EHESS), Paris

Svenja Goltermann, Professor Dr., Historisches Seminar, University of Zurich

Neve Gordon, Professor of International Law, School of Law, Queen Mary University of London

Emily Gottreich, Adjunct Professor, Global Studies and Department of History, UC Berkeley, Director MENA-J Program

Leonard Grob, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, Fairleigh Dickinson University

Jeffrey Grossman, Associate Professor, German and Jewish Studies, Chair of the German Department, University of Virginia

Atina Grossmann, Professor of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, The Cooper Union, New York

Wolf Gruner, Shapell-Guerin Chair in Jewish Studies and Founding Director of the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research, University of Southern California

François Guesnet, Professor of Modern Jewish History, Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies, University College London

Ruth HaCohen, Artur Rubinstein Professor of Musicology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Aaron J. Hahn Tapper, Professor, Mae and Benjamin Swig Chair in Jewish Studies, University of San Francisco

Liora R. Halperin, Associate Professor of International Studies, History and Jewish Studies; Jack and Rebecca Benaroya Endowed Chair in Israel Studies, University of Washington

Rachel Havrelock, Professor of English and Jewish Studies, University of Illinois, Chicago

Sonja Hegasy, Professor Dr., Scholar of Islamic Studies and Professor of Postcolonial Studies, Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin

Elizabeth Heineman, Professor of History and of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies, University of Iowa

Didi Herman, Professor of Law and Social Change, University of Kent

Deborah Hertz, Wouk Chair in Modern Jewish Studies, University of California, San Diego

Dagmar Herzog, Distinguished Professor of History and Daniel Rose Faculty Scholar Graduate Center, The City University of New York (CUNY)

Susannah Heschel, Eli M. Black Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies, Chair, Jewish Studies Program, Dartmouth College

Dafna Hirsch, Dr., Open University of Israel

Marianne Hirsch, William Peterfield Trent Professor of Comparative Literature and Gender Studies, Columbia University

Christhard Hoffmann, Professor of Modern European History, University of Bergen

Dr. habil. Klaus Holz, General Secretary of the Protestant Academies of Germany, Berlin

Eva Illouz, Directrice d’etudes, EHESS Paris and Van Leer Institute, Fellow

Jill Jacobs, Rabbi, Executive Director, T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights, New York

Uffa Jensen, Professor Dr., Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universität, Berlin

Jonathan Judaken, Professor, Spence L. Wilson Chair in the Humanities, Rhodes College

Robin E. Judd, Associate Professor, Department of History, The Ohio State University

Irene Kacandes, The Dartmouth Professor of German Studies and Comparative Literature, Dartmouth University

Marion Kaplan, Skirball Professor of Modern Jewish History, New York University

Eli Karetny, Deputy Director Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies; Lecturer Baruch College, The City University of New York (CUNY)

Nahum Karlinsky, The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Menachem Klein, Professor Emeritus, Department of Political Studies, Bar Ilan University

Brian Klug, Senior Research Fellow in Philosophy, St. Benet’s Hall, Oxford; Member of the Philosophy Faculty, Oxford University

Francesca Klug, Visiting Professor at LSE Human Rights and at the Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice, Sheffield Hallam University

Thomas A. Kohut, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Professor of History, Williams College

Teresa Koloma Beck, Professor of Sociology, Helmut Schmidt University, Hamburg

Rebecca Kook, Dr., Department of Politics and Government, Ben Gurion University of the Negev

Claudia Koonz, Professor Emeritus of History, Duke University

Hagar Kotef, Dr., Senior Lecturer in Political Theory and Comparative Political Thought, Department of Politics and International Studies, SOAS, University of London

Gudrun Kraemer, Professor Dr., Senior Professor of Islamic Studies, Freie Universität Berlin

Cilly Kugelman, Historian, fmr. Program Director of the Jewish Museum, Berlin

Tony Kushner, Professor, Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations, University of Southampton

Dominick LaCapra, Bowmar Professor Emeritus of History and of Comparative Literature, Cornell University

Daniel Langton, Professor of Jewish History, University of Manchester

Shai Lavi, Professor, The Buchmann Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University; The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute

Claire Le Foll, Associate Professor of East European Jewish History and Culture, Parkes Institute, University of Southampton; Director Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations

Nitzan Lebovic, Professor, Department of History, Chair of Holocaust Studies and Ethical Values, Lehigh University

Mark Levene, Dr., Emeritus Fellow, University of Southampton and Parkes Centre for Jewish/non-Jewish Relations

Simon Levis Sullam, Associate Professor in Contemporary History, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, University Ca’ Foscari Venice

Lital Levy, Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Princeton University

Lior Libman, Assistant Professor of Israel Studies, Associate Director Center for Israel Studies, Judaic Studies Department, Binghamton University, SUNY

Caroline Light, Senior Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies Program in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies, Harvard University

Kerstin von Lingen, Professor for Contemporary History, Chair for Studies of Genocide, Violence and Dictatorship, Vienna University

James Loeffler, Jay Berkowitz Professor of Jewish History, Ida and Nathan Kolodiz Director of Jewish Studies, University of Virginia

Hanno Loewy, Director of the Jewish Museum Hohenems, Austria

Ian S. Lustick, Bess W. Heyman Chair, Department of Political Science, University of Pennsylvania

Sergio Luzzato, Emiliana Pasca Noether Chair in Modern Italian History, University of Connecticut

Shaul Magid, Professor of Jewish Studies, Dartmouth College

Avishai Margalit, Professor Emeritus in Philosophy, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Jessica Marglin, Associate Professor of Religion, Law and History, Ruth Ziegler Early Career Chair in Jewish Studies, University of Southern California

Arturo Marzano, Associate Professor of History of the Middle East, Department of Civilizations and Forms of Knowledge, University of Pisa

Anat Matar, Dr., Department of Philosophy, Tel Aviv University

Manuel Reyes Mate Rupérez, Instituto de Filosofía del CSIC, Spanish National Research Council, Madrid

Menachem Mautner, Daniel Rubinstein Professor of Comparative Civil Law and Jurisprudence, Faculty of Law, Tel Aviv University

Brendan McGeever, Dr., Lecturer in the Sociology of Racialization and Antisemitism, Department of Psychosocial Studies, Birkbeck, University of London

David Mednicoff, Chair Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies and Associate Professor of Middle Eastern Studies and Public Policy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Eva Menasse, Novelist, Berlin

Adam Mendelsohn, Associate Professor of History and Director of the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Cape Town

Leslie Morris, Beverly and Richard Fink Professor in Liberal Arts, Professor and Chair Department of German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch, University of Minnesota

Dirk Moses, Frank Porter Graham Distinguished Professor of Global Human Rights History, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Samuel Moyn, Henry R. Luce Professor of Jurisprudence and Professor of History, Yale University

Susan Neiman, Professor Dr., Philosopher, Director of the Einstein Forum, Potsdam

Anita Norich, Professor Emeritus, English and Judaic Studies, University of Michigan

Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas, Professor of Modern European History, University of Santiago de Compostela

Esra Ozyurek, Sultan Qaboos Professor of Abrahamic Faiths and Shared Values Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge

Ilaria Pavan, Associate Professor in Modern History, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa

Derek Penslar, William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History, Harvard University

Andrea Pető, Professor, Central European University (CEU), Vienna; CEU Democracy Institute, Budapest

Valentina Pisanty, Associate Professor, Semiotics, University of Bergamo

Renée Poznanski, Professor Emeritus, Department of Politics and Government, Ben Gurion University of the Negev

David Rechter, Professor of Modern Jewish History, University of Oxford

James Renton, Professor of History, Director of International Centre on Racism, Edge Hill University

Shlomith Rimmon Kenan, Professor Emerita, Departments of English and Comparative Literature, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Member of the Israel Academy of Science

Shira Robinson, Associate Professor of History and International Affairs, George Washington University

Bryan K. Roby, Assistant Professor of Jewish and Middle East History, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Na’ama Rokem, Associate Professor, Director Joyce Z. And Jacob Greenberg Center for Jewish Studies, University of Chicago

Mark Roseman, Distinguished Professor in History, Pat M. Glazer Chair in Jewish Studies, Indiana University

Göran Rosenberg, Writer and Journalist, Sweden

Michael Rothberg, 1939 Society Samuel Goetz Chair in Holocaust Studies, UCLA

Sara Roy, Senior Research Scholar, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University

Miri Rubin, Professor of Medieval and Modern History, Queen Mary University of London

Dirk Rupnow, Professor Dr., Department of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck, Austria

Philippe Sands, Professor of Public Understanding of Law, University College London; Barrister; Writer

Victoria Sanford, Professor of Anthropology, Lehman College Doctoral Faculty, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York (CUNY)

Gisèle Sapiro, Professor of Sociology at EHESS and Research Director at the CNRS (Centre européen de sociologie et de science politique), Paris

Peter Schäfer, Professor of Jewish Studies, Princeton University, fmr. Director of the Jewish Museum Berlin

Andrea Schatz, Dr., Reader in Jewish Studies, King’s College London

Jean-Philippe Schreiber, Professor, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels

Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, Professor Dr., Director of the Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universität Berlin

Guri Schwarz, Associate Professor of Contemporary History, Dipartimento di Antichità, Filosofia e Storia, Università di Genova

Raz Segal, Associate Professor, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Stockton University

Joshua Shanes, Associate Professor and Director of the Arnold Center for Israel Studies, College of Charleston

David Shulman, Professor Emeritus, Department of Asian Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Dmitry Shumsky, Professor, Israel Goldstein Chair in the History of Zionism and the New Yishuv, Director of the Bernard Cherrick Center for the Study of Zionism, the Yishuv and the State of Israel, Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Marcella Simoni, Professor of History, Department of Asian and North African Studies, Ca’ Foscari University, Venice

Santiago Slabodsky, The Robert and Florence Kaufman Endowed Chair in Jewish Studies and Associate Professor of Religion, Hofstra University, New York

David Slucki, Associate Professor of Contemporary Jewish Life and Culture, Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation, Monash University, Australia

Tamir Sorek, Liberal Arts Professor of Middle East History and Jewish Studies, Penn State University

Levi Spectre, Dr., Senior Lecturer at the Department of History, Philosophy and Judaic Studies, The Open University of Israel; Researcher at the Department of Philosophy, Stockholm University, Sweden

Michael P. Steinberg, Professor, Barnaby Conrad and Mary Critchfield Keeney Professor of History and Music, Professor of German Studies, Brown University

Lior Sternfeld, Assistant Professor of History and Jewish Studies, Penn State Univeristy

Michael Stolleis, Professor of History of Law, Max Planck Institute for European Legal History, Frankfurt am Main

Mira Sucharov, Professor of Political Science and University Chair of Teaching Innovation, Carleton University Ottawa

Adam Sutcliffe, Professor of European History, King’s College London

Anya Topolski, Associate Professor of Ethics and Political Philosophy, Radboud University, Nijmegen

Barry Trachtenberg, Associate Professor, Rubin Presidential Chair of Jewish History, Wake Forest University

Emanuela Trevisan Semi, Senior Researcher in Modern Jewish Studies, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

Heidemarie Uhl, PhD, Historian, Senior Researcher, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna

Peter Ullrich, Dr. Dr., Senior Researcher, Fellow at the Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universität Berlin

Uğur Ümit Üngör, Professor and Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Amsterdam; Senior Researcher NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam

Nadia Valman, Professor of Urban Literature, Queen Mary, University of London

Dominique Vidal, Journalist, Historian and Essayist

Alana M. Vincent, Associate Professor of Jewish Philosophy, Religion and Imagination, University of Chester

Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, Head of The Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Anika Walke, Associate Professor of History, Washington University, St. Louis

Yair Wallach, Dr., Senior Lecturer in Israeli Studies School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, SOAS, University of London

Michael Walzer, Professor Emeritus, Institute for Advanced Study, School of Social Science, Princeton

Dov Waxman, Professor, The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation Chair in Israel Studies, University of California (UCLA)

Ilana Webster-Kogen, Joe Loss Senior Lecturer in Jewish Music, SOAS, University of London

Bernd Weisbrod, Professor Emeritus of Modern History, University of Göttingen

Eric D. Weitz, Distinguished Professor of History, City College and the Graduate Center, The City University of New York (CUNY)

Michael Wildt, Professor Dr., Department of History, Humboldt University, Berlin

Abraham B. Yehoshua, Novelist, Essayist and Playwright

Noam Zadoff, Assistant Professor in Israel Studies, Department of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck

Tara Zahra, Homer J. Livingston Professor of East European History; Member Greenberg Center for Jewish Studies, University of Chicago

José A. Zamora Zaragoza, Senior Researcher, Instituto de Filosofía del CSIC, Spanish National Research Council, Madrid

Lothar Zechlin, Professor Emeritus of Public Law, fmr. Rector Institute of Political Science, University of Duisburg

Yael Zerubavel, Professor Emeritus of Jewish Studies and History, fmr. Founding Director Bildner Center for the Study of Jewish Life, Rutgers University

Moshe Zimmermann, Professor Emeritus, The Richard Koebner Minerva Center for German History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Steven J. Zipperstein, Daniel E. Koshland Professor in Jewish Culture and History, Stanford University

Moshe Zuckermann, Professor Emeritus of History and Philosophy, Tel Aviv University

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA)?

The JDA is a resource for strengthening the fight against antisemitism. It comprises a preamble, definition, and a set of 15 guidelines.

Who are the authors?

International scholars in antisemitism studies and related fields, who, from June 2020, met in a series of online workshops, with different participants at different times. The JDA is endorsed by a diverse range of distinguished scholars and heads of institutes in Europe, the United States, Canada and Israel.

Why “Jerusalem”?

Originally, the JDA was convened in Jerusalem by the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute.

Why now?

The JDA responds to the Working Definition of Antisemitism adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) in 2016. “The IHRA Definition” (including its “examples”) is neither clear nor coherent. Whatever the intentions of its proponents, it blurs the difference between antisemitic speech and legitimate criticism of Israel and Zionism. This causes confusion, while delegitimizing the voices of Palestinians and others, including Jews, who hold views that are sharply critical of Israel and Zionism. None of this helps combat antisemitism. The JDA responds to this situation.

So, is the JDA intended to be an alternative to the IHRA Working Definition?

Yes, it is. People of goodwill seek guidance about the key question: When does political speech about Israel or Zionism cross the line into antisemitism and when should it be protected? The JDA is intended to provide this guidance, and so should be seen as a substitute for the IHRA Definition. But if an organization has formally adopted the IHRA Definition it can use the JDA as a corrective to overcome the shortcomings of the IHRA Definition.

Who does the definition cover?

The definition applies whether Jewish identity is understood as ethnic, biological, religious, cultural, etc. It also applies in cases where a non-Jewish person or institution is either mistaken for being Jewish (“discrimination by perception”) or targeted on account of a connection to Jews (“discrimination by association”).

Should the JDA be officially adopted by, say, governments, political parties or universities?

The JDA can be used as a resource for various purposes. These include education and raising awareness about when speech or conduct is antisemitic (and when it is not), developing policy for fighting antisemitism, and so on. It can be used to support implementation of anti-discrimination legislation within parameters set by laws and norms protecting free expression.

Should the JDA be used as part of a “hate speech code”?

No, it should not. The JDA is not designed to be a legal or quasi-legal instrument of any kind. Nor should it be codified into law, nor used to restrict the legitimate exercise of academic freedom, whether in teaching or research, nor to suppress free and open public debate that is within the limits laid down by laws governing hate crime.

Will the JDA settle all the current arguments over what is and what is not antisemitic?

The JDA reflects the clear and authoritative voice of scholarly experts in relevant fields. But it cannot settle all arguments. No document on antisemitism can be exhaustive or anticipate all the ways in which antisemitism will manifest in the future. Some guidelines (such as #5), give just a few examples in order to illustrate a general point. The JDA is intended as an aid to thinking and to thoughtful discussion. As such, it is a valuable resource for consultations with stakeholders about identifying antisemitism and ensuring the most effective response.

Why are 10 of the 15 guidelines about Israel and Palestine?

This responds to the emphasis in the IHRA Definition, in which 7 out of 11 “examples” focus on the debate about Israel. Moreover, it responds to a public debate, both among Jews and in the wider population, that demonstrates a need for guidance concerning political speech about Israel or Zionism: when should it be protected and when does it cross the line into antisemitism?

What about contexts other than Israel and Palestine?

The general guidelines (1-5) apply in all contexts, including the far right, where antisemitism is increasing. They apply, for instance, to conspiracy theories about “the Jews” being behind the Covid-19 pandemic, or George Soros funding BLM and Antifa protests to promote a “hidden Jewish agenda.”

Does the JDA distinguish between anti-Zionism and antisemitism?

The two concepts are categorically different. Nationalism, Jewish or otherwise, can take many forms, but it is always open to debate. Bigotry and discrimination, whether against Jews or anyone else, is never acceptable. This is an axiom of the JDA.

Then does the JDA suggest that anti-Zionism is never antisemitic?

No. The JDA seeks to clarify when criticism of (or hostility to) Israel or Zionism crosses the line into antisemitism and when it does not. A feature of the JDA in this connection is that (unlike the IHRA Definition) it also specifies what is not, on the face of it, antisemitic.

What is the underlying political agenda of the JDA as regards Israel and Palestine?

There isn’t one. That’s the point. The signatories have diverse views about Zionism and about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, including political solutions, such as one-state versus two-states. What they share is a twofold commitment: fighting antisemitism and protecting freedom of expression on the basis of universal principles.

But doesn’t guideline 14 support BDS as a strategy or tactic aimed against Israel?

No. The JDA’s signatories have different views on BDS. Guideline 14 says only that boycotts, divestments and sanctions aimed at Israel, however contentious, are not, in and of themselves, antisemitic.

So, how can someone know when BDS (or any other measure) is antisemitic?

That’s what the general guidelines (1 to 5) are for. In some cases it is obvious how they apply, in others it is not. As has always been true when making judgments about any form of bigotry or discrimination, context can make a huge difference. Moreover, each guideline should be read in the light of the others. Sometimes you have to make a judgement call. The 15 guidelines are intended to help people make those calls.

Guideline 10 says it is antisemitic to deny the right of Jews in the State of Israel “to exist and flourish, collectively and individually, as Jews”. Isn’t this contradicted by guidelines 12 and 13?

There is no contradiction. The rights mentioned in guideline 10 attach to Jewish inhabitants of the state, whatever its constitution or name. Guidelines 12 and 13 clarify that it is not antisemitic, on the face of it, to propose a different set of political or constitutional arrangements.

What, in short, are the advantages of the JDA over the IHRA Definition?

There are several, including the following: The JDA benefits from several years of reflection on, and critical assessment of, the IHRA Definition. As a result, it is clearer, more coherent and more nuanced. The JDA articulates not only what antisemitism is but also, in the context of Israel and Palestine, what, on the face of it, it is not. This is guidance that is widely needed. The JDA invokes universal principles and, unlike the IHRA Definition, clearly links the fight against antisemitism with the fight against other forms of bigotry and discrimination. The JDA helps create a space for frank and respectful discussion of difficult issues, including the vexed question of the political future for all inhabitants of Israel and Palestine. For all these reasons, the JDA is more cogent, and, instead of generating division, it aims at uniting all forces in the broadest possible fight against antisemitism.

About JDA

In 2020, a group of scholars in Antisemitism Studies and related fields, including Jewish, Holocaust, Israel, Palestine and Middle East Studies, came together under the auspices of the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute to address key challenges in identifying and confronting antisemitism. During a year of deliberations, they reflected on the use of existing tools, including the working definition adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), and its implications for academic freedom and freedom of expression.

The JDA organizers and signatories represent a wide range of academic disciplines and regional perspectives and they have diverse views on questions related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But they agreed on the need for a more precise interpretive tool to help clarify conditions that are antisemitic as well as conditions that are not definitive proof of antisemitism.

Coordinating group

Seth Anziska, Mohamed S. Farsi-Polonsky Associate Professor of Jewish-Muslim Relations, University College London

Aleida Assmann, Professor Dr., Literary Studies, Holocaust, Trauma and Memory Studies, Konstanz University

Alon Confino, Pen Tishkach Chair of Holocaust Studies, Professor of History and Jewish Studies, Director Institute for Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Emily Dische-Becker, Journalist

David Feldman, Professor, Director of the Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, Birkbeck, University of London

Amos Goldberg, Professor, The Jonah M. Machover Chair in Holocaust Studies, Head of the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Brian Klug, Senior Research Fellow in Philosophy, St. Benet’s Hall, Oxford; Member of the Philosophy Faculty, Oxford University

Stefanie Schüler Springorum, Professor Dr., Director of the Center for Research on Antisemitism, Technische Universität Berlin

Videos

JDA – Highlights

JDA – Full conversation

Copyright © 2021 JDA | Design by LotteDesign

Jewish Voice for Peace Statement, April 5, 2021

We believe in a world where we are all safe and cherished—a world without racism, without antisemitism, and without Islamophobia. As fascist, racist, and authoritarian governments and political parties increasingly amass power around the world, we are more committed than ever to the work of building a world where justice, equality, and dignity are accorded to all people without exception.

We write this statement with urgent concern about the ongoing attempts of the Israeli government to evade accountability for its human rights abuses and violations of international law by levying accusations of antisemitism at Palestinians and those who advocate for Palestinian rights. Not only does this silence Palestinians and their advocates, but it also jeopardizes Jewish safety and the struggle to dismantle antisemitism.

The most prominent example of this dangerous campaign is the attempt to impose the flawed and widely discredited International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism on governments, public institutions, universities, and civil society. The IHRA definition is not designed to protect Jewish communities from the rising bigotry and racist attacks we face, predominantly carried out by white supremacists. Instead, it has been employed in many countries as a bludgeon to suppress advocacy and academic freedom. Scores of Palestinian, Israeli, civil society, and human rights organizations from across the globe, as well as academics, writers, and activists—including one of the IHRA’s original authors—have condemned its anti-democratic and repressive impact.

In this context, we welcome the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA) as a useful corrective to the dangerously flawed IHRA definition. If an institution believes it needs a definition, the Jerusalem Declaration is a vastly improved replacement for the IHRA. Drafted and endorsed by many of the world’s most preeminent Jewish studies scholars, it opens space for debate, champions freedom of speech, and refutes the most misleading aspects of the IHRA definition. However, in attempting to remedy the deceptive claims of the IHRA definition, the JDA falls into the trap of situating Israel-Palestine at the centre of conversations about antisemitism. If the drafters required this special scrutiny to respond fully to IHRA, then they should have included representative Palestinian perspectives and analyses in shaping the document, without which the JDA remains incomplete. This disproportionate focus risks contributing to the intense policing of discourse on Israel-Palestine, and distracting from the real dangers we face as Jews today from white supremacists and the far-right.

Most importantly, we are acutely aware that defining antisemitism does not actually do the work of dismantling antisemitism. Legislating a static definition for any particular form of bigotry weakens our society’s efforts to combat discrimination across different contexts and over time. Instead of trying to codify definitions of antisemitism, we call on progressives around the world to commit to dismantling it alongside all forms of oppression and bigotry. To create safety and freedom for all people, including Jewish people, we offer these principles and practical steps:

- Do not isolate antisemitism from other forms of oppression.

Situate your work to dismantle antisemitism within the broader struggle against all forms of racism and oppression. Antisemitism is embedded in white supremacy, and is part of the machinery of division and fear used to keep us isolated and vulnerable—the same machinery that is used to target Black people and other people of color, people who are Muslim, immigrants, Indigenous communities, and others. Isolating antisemitism ignores the central threats faced by these communities under white supremacy, erases the lived experiences of Black Jews and other Jews of color, and atomizes a struggle that must be united to succeed. Act from the principles that oppression is intersectional and that justice is indivisible. - Challenge political ideologies that foment racism, hate, and fear.

Refuse and challenge fascist, white nationalist, and far-right ideologies leading to murderous violence. These conspiratorial and dangerous beliefs are wielded to divide and sow fear across communities, and to reinforce and maintain white supremacy. Cede no ground to the leaders, institutions, and politicians who promote these ideologies and gain power by breeding violent antisemitism, racism, Islamophobia, and xenophobia. - Create environments that affirm and celebrate all expressions of cultural and religious life.

Institute policies and practices that actively embrace, not just tolerate, cultural and religious diversity. White Christian hegemony structures many of our societies, lives, relationships, and institutions. By framing all communities that are not white and Christian as the “other,” this feeds exploitation, hatred, and discrimination. Push back on this harmful reality by assessing your community or organization’s policies and building affirming, inclusive spaces where Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, Buddhist and all other faith communities can thrive and belong. - Make undoing all forms of racism and bigotry both policy and daily practice.

Establish racial justice, religious inclusion, and social equity as central pillars for setting policy and making decisions—in organizations, institutions, and legislation. Until our entire society is transformed to the point where racism and antisemitism are truly eradicated, it is up to all of us to create open spaces, rooted in the fabric of daily practice, for anti-racist educational initiatives, curriculums, and frameworks. If we do not make undoing white supremacy, including anti-Black racism, antisemitism and islamophobia, a part of our daily lives, we will never achieve the just future we want. - Practice safety through solidarity, not law enforcement.

Resist calls to respond to violence against Jewish people by increasing police presence. Increased policing will harm some of the most vulnerable members of our communities, including Jewish people of color. Instead, invest in strategies, practices, and plans that build protection and safety for all our communities, without increasing the power and presence of increasingly militarized law enforcement. Our history shows that freedom and safety for any of us depends on freedom and safety for all of us.

Signed by:

Jewish Voice for Peace (US)

Independent Jewish Voices (Canada)

Manchester Jewish Action for Palestine (UK)

Jewish Liberation Theology Institute (Canada)

Sh’ma Koleinu – Alternative Jewish Voices (New Zealand)

Boycott from Within (Israeli citizens for BDS)

Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East (Germany)

Jews against the Occupation (Australia)

French Jewish Peace Union (Union Juive Française pour la Paix) (France)

Jews Say No! (USA)

Collectif Judéo Arabe et Citoyen pour la Palestine (France)

International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network

Een Andere Joodse Stem – Another Jewish Voice (Flanders, Belgium)

Scottish Jews Against Zionism (Scotland)

As the Spirit Moves Us (a Jewish Justice organization)

Tikkun Olam Chavurah